According to the SPI index for week ending 18-Jun, national flour prices have jumped ahead by 17 percent over the last four weeks, with the highest increase of 30 percent witnessed in provincial capital, Lahore. A price surge following the end of harvest season has naturally driven the public to smell foul, although it appears to be a classic case of bureaucratic plans gone wrong.

There are only two explanations for why Pakistan may face a wheat shortfall in 2020. One, official estimate of 25 million tons output achieved in FY20 - as reported over the past 6 months in meetings of ECC, MNFS&R, and most recently in the Annual Economic Survey – is false. Or, the policymakers are clueless about domestic wheat demand and consumption trends.

While they have botched up the management this season, this is not an indictment of incumbents alone. For the past 20 years, official publications have calculated domestic consumption at 120-125kg per capita, which appears to be an extrapolation based on global averages, even as no research, census, or survey has been conducted to corroborate the same for domestic economy.

Which brings us to the colossal mishandling that was wheat commodity operations this year. The story begins with the official output target. Although it is correct that the shortfall in production (7.7 percent) is highest in 12 years, target of 27+ million tons – fixed in Oct-19 - was set in thin air, in absence of any regulatory or fiscal measures to turn it into a reality (taken at the time).

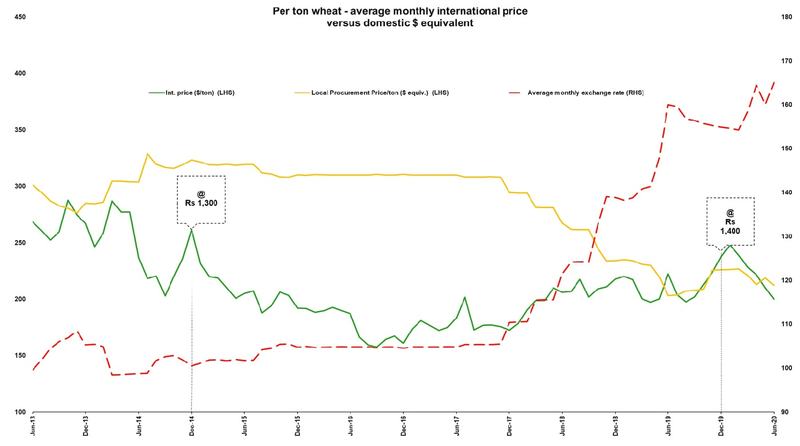

It should be recalled that over the past decade, crop yield has stagnated at 2.8 tons per ha. While cost of production has increased in tandem with inflation, economic returns to producers have come at a standstill owing to a national food security policy which encourages cultivation (by guaranteeing a purchase price), but restrains farmers from reaping benefits of advantageous market movements.

It is little surprise then that the unreasonably high production target was missed by a wide margin, even as output level achieved is 2.5 percent higher than last year. That should have hit brakes on wheat prices, which had already increased by 24 percent during the 12-month period between Dec 2018 and 2019.

Which brings us to the second blunder: the unrealistic procurement target of 8.25 million tons (20 percent higher than previous year), set at the beginning of harvest season in March earlier this year, along with an increase in official purchase price by Rs100/40kg after a lag of 5 years (see illustration).

There is little doubt that both measures were taken with the noblest of intentions. Instead, they ended up having an unintended (yet an obvious) consequence of encouraging stocking at the farm level at the expense of open-market commercial transactions between growers and whole sellers.

It is as if the universe was also not on the side of officialdom this year. The country was hit with the Covid-19 led lockdown during the peak harvest season, which naturally affected government procurement operations. By April-end, both PASSCO and provincial Food Departments, especially in Punjab, struggled to meet procurement targets, leading to a high-level meeting on 05May between civil and military authorities in the province. That fuelled all sorts of conspiracy theories regarding low stock positions with Food departments, leading to another fatal policy error.

In mid-May, the provincial government imposed a cap on private storage of wheat at 25 maunds (1 tons), accompanying it with strict penalties for “hoarders” found in violation of the law. Of course, it failed to account for widespread rural private storage that takes place to cater to on-farm consumption for the remainder year. And in the process, cemented belief of market players that government stocks were insufficient to meet domestic needs this year.

What has followed since is a flurry of missteps that would be comical if not tragic. In May end, Pakistan Flour Mills Association (PFMA) briefly went on a strike on account of non-availability of wheat. Since then, federal government keeps reassuring lobbying groups that wheat is in adequate supply. Retail prices – at least to the extent of Punjab – are periodically brought under control by announcing an official price list and bringing down the hammer of district management, only to run amok later as witnessed during past four weeks.

Except, talk to any suppliers of wheat in Wholesale Mandis and they refuse to quote any rate for a commodity that they claim is simply not there (“we have no stocks”, claimed at least 5 registered whole sellers from Lahore in telephonic conversations with BR Research). This indicates that the recently announced measure to remove restrictions on wheat import by private sector at a time when global commodity prices are under pressure, is sensible.

But only to the extent that it is used to send a price signal to stockists that imported wheat shall soon be available in domestic market, aimed to force their hand into releasing stocks. Except, competition goes both ways. After a lull of 4 years, domestically produced wheat once again became competitive internationally owing to the resetting of foreign exchange regime in Pakistan that led to devaluation of Rupee by more than one-third since June-2018.

That means for stockists, it is almost equally lucrative to export wheat in current times as it is to sell it domestically, except export is banned. Add to this the theories about output shortfalls, missed procurement target, fears of smuggling via Afghanistan, and cap on private storage – and the erratic behaviour of domestic wholesale and retail prices suddenly begins to make sense.

‘A reform-minded government gave way to over-regulation; in the process, killing all hopes of fair price discovery through market mechanism’. So shall read the foreword of the inquiry report on the next wheat crisis, playing right in front of our collective eyes today.

Comments

Comments are closed.