Pakistan’s best hope at putting an end to cyclical mismatches between wheat supply and demand is for government to exit procurement operations, create ease for imports by liberalizing tariffs, and allow market-based price discovery. But reforming wheat market does not seem to be on the agenda under the incumbents.And it certainly won’t happen a year before general election, in the throes of peak global commodity prices (in a decade). Surprisingly enough, the best recourse in the short-run – to avoid another local shortage – may be to fix a higher intervention price. Self-contradictory? Consider the following.

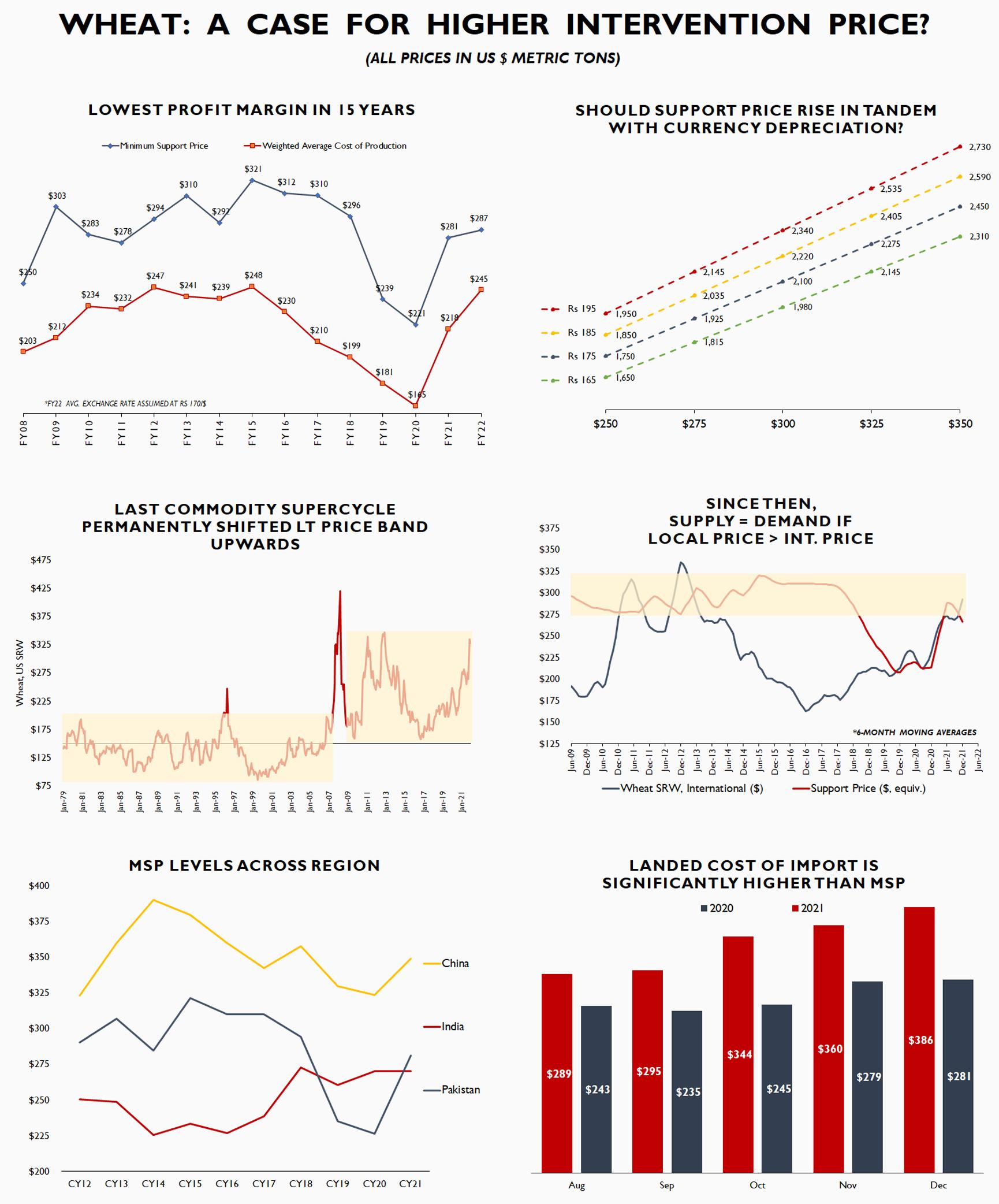

Between FY12 – FY18, local wheat output and consumption remained at par, with negligible imports. This period coincided with grain prices bottoming out in the international market. Local prices on the other hand, held steady – a consequence of both:a downward sticky minimum support price regime, and an artificially overvalued exchange rate.

Since late 2018 when Pakistan adopted a market-based exchange rate, wheat prices in the local market have declined substantially in dollar terms, trading at par – and for a short-while even below – prices in the international market. This price parity has coincided with local supply falling short of domestic consumption, manifesting itself in a local price spiral. Between Aug-18 and Dec-21, wheat prices rose by 80 percent in local wholesale market (WPI).

This inverse correlation between domestic wheat availability and price competitiveness in the international market is not without cause. An obvious possibility is that lower prices in dollar terms leads to higher disappearances as incentive foroutward smuggling grows. However, an official export ban means that both the extent and impact of any such cross-border disappearances remains unknowable. Another possibilityis that currency depreciation and price control may reduce the profitability of wheat crop in dollar terms, driving farmers to substitute cropswhose prices adjust more readily to movements in international market or in exchange rate.

Either way, what is patently obvious is that every time exchange rate comes under significant pressure, local wheat market falls into disequilibrium, which cannot be immediately addressed through market forces due to barriers to trade. Eventually, the administration is forced to increasing MSP significantly – as it did by 50 percent in FY08, or by 30 percent in FY21, permanently raising prices for domestic consumers (as support pricesare never revised downwards).

Like Sisyphus’ rock, local market can be emancipated from the cyclical disequilibrium if policymakers were to let the market forces reign free; let imports flow in; and have stockists/exporters ‘officially’ make one-off gains each time local and international markets are trading at significant differential. But the incumbents most certainly lack the courage to undertake reforms of such import, especially not in the year leading up to election. Also, international prices’ recent flirtation with fresh peak means that the timing may not be right; more so, with a war looming between Russia and Ukraine, two of world’s six largest wheat producers.

Nevertheless, the differential against international price may once again widen in the coming months, especially if the currency continues its downward slide. Meanwhile, the federal government has raised MSP by only 8 percent for the upcoming season (in rupee terms). For farmers, this season the price is well below market equilibrium range ($275 to $325 per ton over the last decade), inflationary pressure means that cost of wheat production in dollar terms is highest in the last seven years. At current MSP of Rs 1,950 per 40kg, profit margin for farmers shall be lowest in the last 15 years!

Government’s decision to not raise MSP abnormally is also not without cause. Official rate for wheat has already been raised by 50 percent since PTI came to power. At this price, public sector commodity operations debt is all set to exceed Rs 1 trillion for the first time in history, as cost of debt servicing alone may round up to Rs 60 billion or above! And that’s just accounting for local procurement; in case of a shortfall and imports through TCP, cost to the exchequer shall witness yet more slippages.

Put the pieces of the puzzle together, it appears likely that the PTI government may face yet another wheat crisis come mid-2022, whether it is due to shortfall in production, farmers’ unwillingness to sell to Food departments, disappearances due to smuggling, or expensive imports. So, what can it do to ease the pain in the short-run?

Raise the minimum support price for the upcoming season, at least up to $300 per ton (rupee equivalent); lower government procurement target substantially to minimize loss on commodity operations;instruct SBP to facilitate in-season buying by private sector through raising financing limits;and allow post-season import by private sector to counter threat of disappearances through smuggling. A higher support price with lower procurement target will in effect act as an intervention price, minimizing risk of farmer exploitation by private sector due to distressed sales. And let this be a first step towards a phased but very permanent exit of public sector from the messy wheat market.

Free market is an operating system. Market based exchange rates would only bring price stability to commoditiessuch as wheat - if pricing of goods is also market-based, not administratively controlled. But here in Pakistan,the public has become victim to an unenviable situation. The policymakers arekeen to make the market-based exchange rate stay, without offering the nuts and bolts of what makes it work in other countries. By not liberalizing goods markets alongside exchange rate regime, policymakers have made a bad problem worse.The state is unwilling (or unable due to reasons of political expediency) to let go off administrative controls over goods markets. This anomaly won’t last for too long;and something will have to give, sooner or later.

In the meantime, the public is left with remedies that are akin to palliative care for terminal cancer patients.Raising wheat MSP (or intervention price) is one such solution. But such is also the cost of systemic governance failure.

Comments

Comments are closed.