Food group exports during FY20 have in no way disappointed. Over the last decade – on the other hand – they disappointed thoroughly. According to Advance Releases by PBS, food group exports saw earnings trimmed by the smallest margin compared to other major commodity groups such as textile, petroleum, or surgical goods.

In a year of pandemic led pandemonium, that’s good news. Even better news is that excluding subsidy-based exports of wheat and sugar in past years, food group exports in fact managed to grow by 1.1 percent despite lockdown and a secular slowdown in global trade.

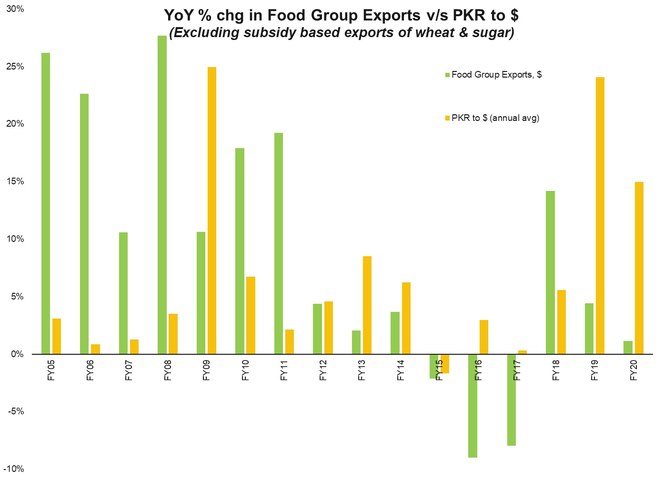

But that’s where the good news ends. Quantum of exports also expanded (or at least held its ground) in major segments such as basmati rice, fruits, and meat; that much was expected. Past episodes of strong currency devaluation indicate that commodity-based exports are usually the first to gain from sudden improvement in price-competitiveness. Note that the extent of currency devaluation since FY18 is the largest for at least the past two decades.

Yet, unlike the last devaluation episode of FY09-FY10, growth in food group/commodity exports during the past two fiscals has been puny, if not dismal. While optimists may be quick to attribute stunted growth during FY20 to Covid-19; were it not for the subsidies extended to surplus output of wheat and sugar, food group commodity exports would have in fact declined during FY18 & FY19, when the precipitous decline in currency value began.

Understandably, lack of improvement in exports is no reason to keep currency overvalued, for if exports are stagnant, an overvalued currency will only further exacerbate the trade deficit as witnessed during the last regime. However, the failure to improve export earnings – especially that of bottom-of-the-pyramid primary commodities – despite massive devaluation is a missed opportunity that raises several questions.

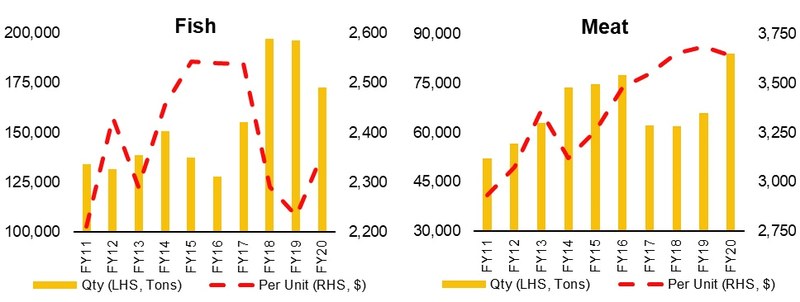

Did weak commodity prices play a role? Partly. Back in FY10-11, unit price of basmati rice – Pakistan’s only high-value crop - averaged at close to $800 per ton, which in FY20 came out at just $522 per ton. In fact, basmati prices are on a decline for at least past three years, which does make the gain in volume during the same period an achievement.

Curiously, Pakistan has in fact lost volume on its largest food group exports – Other or Irri & hybrid rice varieties. Recall that Other rice had become the largest food group exporting product by a wide margin, contributing as much as one-third of total category earnings. Yet, despite an annual 3 percent increase in per ton prices fetched by Other rice over the past four years, volume exported has been on a downward trajectory, falling short by 3.5 percent on average every year.

And that draws attention to the productivity and capacity challenge endemic to Pakistan’s commodity-based exports. While a leading competitor in basmati, Pakistan’s contribution to global Irri and hybrid rice trade is puny. Because Irri/hybrid and basmati have vastly different target markets, there is also no inverse relationship in global demand. The unfortunate trend, however, is explained by Pakistan’s weak capacity to export, which fails to cater to demand when the opportunity presents itself in the form of currency devaluation and domestic producers suddenly discover a newfound price competitiveness.

The story of “non-rice” other half of food group exports is no different. Meat exports, for example, are back in competition in Middle Eastern markets based on pricing. As Faisal Hussain, CEO of The Organic Meat Company Limited explained in an interview to BR Research, Pakistani players undercut both each other and the competition by offering lower rates backed by better currency terms. There is little effort to develop and penetrate the market on durable basis, such as value-addition and supply chain development. Meat export category, for example, would do well to seek both licenses and cold chains for by-sea exports, yet exporters may be happier in making a quick buck.

Which brings the story to the second, yet possibly a more menacing threat endemic to all of Pakistan’s export-oriented industries. Business diversification by Pakistani exporters – both medium and large-scale alike - over the past 15 years, has turned Pakistan’s exporting classes whether textile, rice, meat, or surgical instruments, into seasonal exporters. While diversification as a financial strategy is a valuable idea to maximize returns on portfolio allocation, it has inadvertently cost country’s exports – both in terms of earnings and business focus.

Over the past decade, traditional exporting firms/groups have flocked to other industries such as real estate, power and energy (IPPs), equities, hospitality, domestic retail & shopping malls, etc in search of better returns. This reallocation of finite investment capital has come at the cost of expansion in export-oriented segments. While the outcome for Pakistan’s largest exporting sector textile has been fairly obvious as it remains stuck in low value-added products, food group commodities performance over the past two years must come as a ruder shock.

That over 50 percent devaluation of currency in two years has proven insufficient to meaningfully improve the quantum of primary commodities whether rice, fish, fruits, vegetables or meat, whilst still others such as wheat and sugar require subsidies points towards the deep productivity challenges that have resisted improvement in crop yields. Far from gaining on food group exports during a future commodity price boom, the productivity challenge may soon turn Pakistan into a food-insecure nation, chaotically subsidizing and banning food exports from year to one another to deal with domestic shortfalls. If that sounds too pessimistic, look no further than wheat and sugar.

Comments

Comments are closed.