Of cartels, competition and consumers

Last week, cement prices were abruptly raised by an average Rs55 per bag across markets in Punjab and KP indicating that the cement cartel was back in session. This comes after months of lethargic demand in many markets, and cement manufacturers racing to consumers to sell off excess cement at reduced prices, evidently finding it against their individual benefits to keep colluding. Millions of tons of new capacities had been added while demand was simply not keeping up—it was natural to go their separate ways, each vying for a piece of that proverbial shrinking pie. So why is the cartel back now?

Cartelilization is as old as trade itself—in some instances nefarious and dangerous and in others not as menacing but still conspiratorial and unfair, hurting markets and consumers alike. Pakistan is certainly no stranger to cartels, having many of its influential businesses collude on prices and volumes in order to maximize profits whilst also seeking rent with impunity through subsidies and tax reductions. The question to ask is: what breaks a cartel and what strengthens it?

A cartel functions on a commitment—which may even be implicit or tacit that volumes will be decided and/or prices will be fixed. This commitment comes with strong information sharing, with a central body organizing the cartel, and the understanding that smaller or new players will follow suit of the larger ones; happy to participate and get what they can.

Nobody would deny the existence of a cement cartel confronted with actual data (read more: “There exists a cement cartel”, July 11, 2017) and some historical understanding. Expansions are always done in phases or waves where nearly all players expand capacities during a given period of time. Though capacity utilization varies amongst players, bigger players have higher utilization and smaller players have lower, they all enjoy the space deliberately carved out for them. It is uncommon for any new players to enter the industry, despite there being space in the market for entrants and the high margins the industry boasts during peak demand.

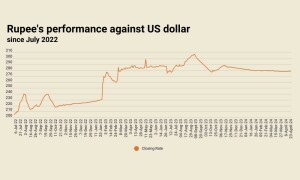

Meanwhile, exports are kept only to diversify the sales mix to an extent when domestic demand drops, they can be sought. But exporting markets breed competition specially where commodity goods are concerned. A simple calculation suggests that last year cement manufacturers were fetching 1.7x times more in rupee value when they sold cement locally. This was a time of weak domestic demand and cement manufacturers had to ramp up exports. The actual differential is probably higher (read more: “Cement exports: the wrath of competition”, Dec 18, 2019).

Ultimately though, the weakness of a cartel is freedom and competition that is inherently present in the market. When the market is faced with oversupply, it is imprudent to keep colluding. It was in fact last year when many players went into expansion that the All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers Association (APCMA) stopped publishing its monthly data on its official website because agreement amongst players was in short supply. There was an information breakdown.

Evidently, the solution here is simple. Even if the Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) cannot prove injury to the market through collusion practices, it does not matter. Allow imports (remove duties) and allow new investments into the industry by creating an efficient regulatory environment that makes entry easier.

In the present situation, one must make an important note. Rising construction costs right now cannot be good. This is a time when PM Imran Khan is looking at housing and construction as a safe bet out of the crippling jobs environment. He has offered countless benefits for investments to flow into the sector, including subsidies to push affordability which will quickly be offset by the rise of steel and cement prices. Builders will not absorb this incremental cost. On the one hand, it makes sense why cement prices were raised—demand is expected to propell post construction package announcement; but on the other hand, it will be that much harder to create affordable housing choices for those households who really need them if prices keep going up. Should prices be regulated, no! But should the market be opened, most definitely yes.

Comments

Comments are closed.