Leaving agriculture behind

Urban bias in policymaking is responsible for the decline in agriculture productivity in Pakistan. Malik Afaq Tiwana, CEO of Farmers Associates Pakistan, brought this to light in his recent interview with BR Research. Pause for a moment, and dwell on that thought, and it will soon be clear that Mr. Tiwana is spot on, for almost the entire discourse on Pakistan’s economy and society has an urban bias, even as Pakistan’s decades-old pursuit of modernisation and urban development remains in vain. (See Brief Recording section 6 Mar 2020)

On the one hand, the media has an urban bias. Because the rural poor are not the biggest market for goods and services whose advertisements provide sponsorship, and because who wants to see buffalo problems on TV! That bias alone creates a self-perpetuating bias towards urban issues by way of ignoring those rare voices who raise rural and agricultural concerns.

It is only when famine hits a rural district (which makes for a hot political story) or when food price hike affects urban consumers, agriculture and rural affairs make it to the news. Case in point: rural inflation last month was still 14.2 percent – as high as the headline number in January 2020 which caused a lot of uproar – whereas rural food inflation in February stood at 19.7 percent which is as high as January’s peak in urban food inflation. Yet because urban food prices softened - as did the headline number (because of higher urban weight in national CPI) - the issue is now off the roster.

On the other hand, nearly all think tanks, policy research institutes, business chambers and associations display an urban bias. Official development assistance by donors too has an urban bias. And even independent economists care less to see outside textile, special economic zones, or other select few industries or urban themes (such as cities governance) when they are not exhibiting macro-obsessions. Similar is the case with higher education and research, where agricultural universities are much smaller in number and rather poor in quality.

Meanwhile, farmers and other members of rural community are neither well represented, nor well financed to draw the attention of ruling and societal elite to rural troubles. Granted, that some big farmers are members of federal and provincial legislatures, and theoretically have the best possible representation. But the reality is that farm sizes in Pakistan are much smaller than most people imagine; average farmer has much smaller land holdings and accordingly not well represented in power corridors.

Make no mistake. Agriculture is not as simple as it appears to be. In the livestock sector, for instance, breeds take decades to be improved, and once the animal falls sick it doesn’t recover its productivity as swiftly as an industrial plant after a BMR exercise or part replacement.

Or in the farming sector, sometimes hopelessly useless varieties save millions from hunger or otherwise create exportable surplus, as did the famous PI-178383 wheat variety that was used to make the crop disease resistant in the US more than fifty years ago. Today that “useless wheat” now dominates the entire Pacific northwest. Considering that there are thousands of varieties, and a long list of unknown unknowns emerging from climate change and changes in biodiversity, the importance of focusing on agriculture and related technology cannot be overstated.

These are just some of the examples to shed light on the underappreciated farming complications relating to weather, seed yield, farm technology adoption which often varies with farm size, utilisation of water, pesticides, fertiliser, and so forth – the economic aspect of which is also understudied.

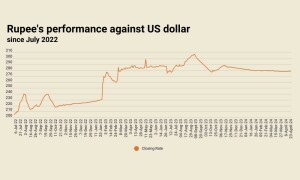

For instance, nearly all input costs – seeds, pesticides, phosphate fertiliser, diesel for running farm equipment – for any half decent farmer in Pakistan are pegged to the exchange rate since all of these or its key ingredients are imported. Which means that the recent exchange rate depreciation has either squeezed farmers’ margins or stoked food inflation. Yet the issue is not even on the public agenda as is usually the case for other goods produced by urban society.

This is not to romanticise about real or perceived serenity of rural life. This is a call for action. Not only because the price of sugar broke General Ayub’s back, or because an army marches on its stomach or because hunger is more savage than cannons. But also, because a surge in agriculture productivity has been historically essential to kick start the process of industrialisation.

Save for the likes of Singapore, UAE, hardly any major economy has been able to industrialise without first increasing its agriculture productivity. Which is why Adam smith had called industry the offspring of agriculture, since improvements in latter helped reduce poverty, and created exportable surpluses that financed industrial development while freeing up labour from land use.

Granted, that in some grand utopian future Pakistan can find comparative advantage in industries, and in mobile apps valued at billions of dollars. Or have scores of lab-based farm production or even vertical farming in the cities. But until that fancy becomes real, policymakers must not lose sight of food and agriculture. (See also BR Research’s ‘Farming our future’ 27 Jun 2019, ‘Regulating food quality & standards’, Feb 10, 2020, ‘The battle for Pakistan’s farms’, Nov 27, 2019)

Comments

Comments are closed.